Is Christian Nationalism the key for understanding all our problems? Or is it the solution?

When it comes to “Christian Nationalism”, it all depends on who you ask (and I’m talking specifically of American Christian Nationalism of the USA).

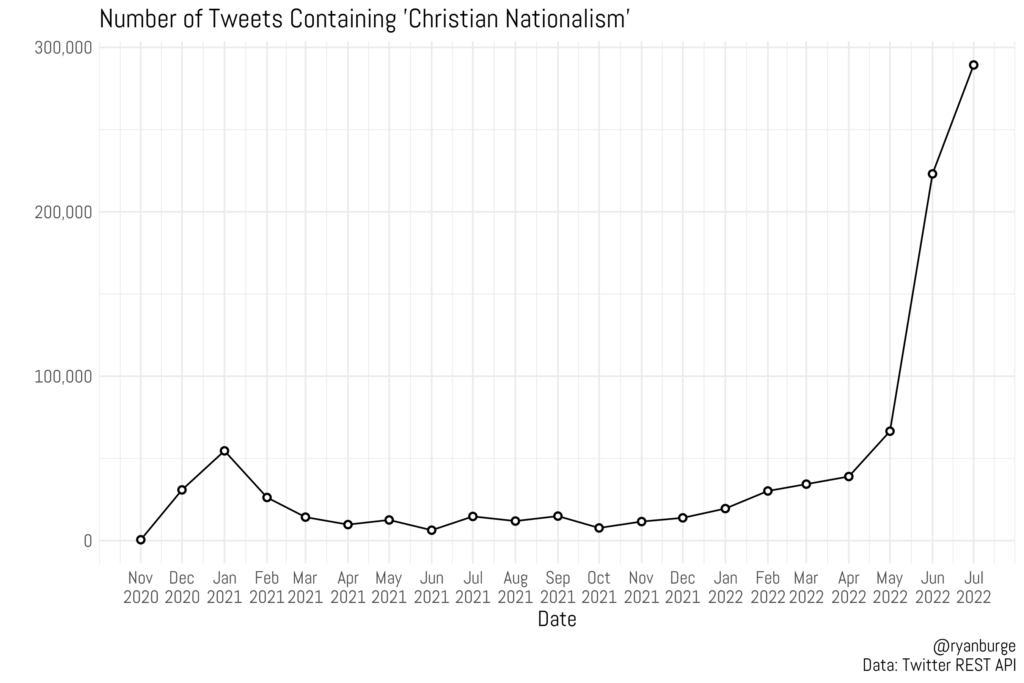

You might have seen a dramatic spike in conversation about “Christian Nationalism” depending on where you are online.

Thankfully, most people don’t live on twitter.

But even if they don’t use the term, for some people, Christian Nationalism (as predominately white and probably racist) is the new key to understanding the rise of Trump and a label for all that ails American politics.

And for others, Christian Nationalism is just a commonsense stance needed to preserve the legacy of America.

But before we can examine Christian Nationalism, we must first as about the “what” and the “why” of nationalism.

This and following posts are pulling from Paul Miller’s recent The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism. I’ll be interviewing him on September 26th (details here soon).

Also, jump on the free webinar asking “Are We A Christian Nation” on Thursday, Sept. 22nd with Dr. David Fitch.

Why Nationalism Now?

Every nation chose sides in an ideological struggle during World War II and the Cold War. You and your country were either for capitalism or for communism. You were either for democracy for and totalitarianism. For freedom or for tyranny. There was no middle ground.

This decades long battles submerged cultural, regional, and religious identities with individual nations.

But when the Cold War ended, and with rising globalization, democracy and freedom did not just win out. Instead, those submerged cultural, regional, and religious identities emerged within and between nations. Around the world this caused civil wars, genocides, and revolutions.

Within this destabilizing context, nationalism all around the world stepped forward in the name of unity. Nationalism is a response to globalization outside the nation and tribalism within it. Nationalism stands against those outside forces tearing the nation down, and against those forces within a nation tearing it apart.

For ordinary people who feel economically threatened by globalization, and who feel cast aside or called out within a nation, the nationalist defense of common values and cultural pride seems quite reasonable. And this is especially true for conservatives who see in both the globalizing trends and critique of the nation by social justice warriors as merely two coins of the same progressive politics.

Against all that, Why is it so bad to embrace some form of nationalism? these conservatives might think.

Whether justified or not, nationalism is a response to a perceived threat, the threat to one’s individual and national well-being. And if our consumer and therapeutic culture has taught us it is that threats to your well-being must being eliminated in our pursuit of happiness.

But what exactly is nationalism?

What is Nationalism?

This is Miller’s condensed definition of nationalism:

“Nationalism is the belief that humanity is divisible into internally coherent, mutually distinct cultural units which merit political independence and human loyalty because of their purported ability to provide meaning, purpose, and value in human life; and that governments are supposed to protect and promote the cultural identities of their respective nations.”

That sounds great—or confusing.

So what does that really mean?

Miller breaks his definition of nationalism into four points, or four common assumptions.

The Four Assumptions

Assumption #1: Humanity is divisible into cultural units, which we call nations.

Nations are not merely territories under a common rule (no matter how that happened historically). Rather a nation has a common “culture” made up of ethnicity, language, or religion that make up identifiable shared traits.

On this view, a nation is not primarily a physical areas governed by the same set of laws. Rather a nation is primarily made up less tangible realities like customs, language, ethnicity, and religion—which all shift over time.

Assumption #2: Political sovereignty is a moral imperative

This is the idea that every cultural unit should have a political state that represents it to and in the world.

Or the ideas is that every nation (a cultural substance) should have a state (a political expression).

Assumption #3: States should have jurisdiction over its culture identity.

This idea means that the government should regulate ways to conserve and protect the cultural substance (the shared traits from assumption #1).

This is part of the circular nature of nationalism. On the one hand, the culture or ethnicity comes first, and the “national” government comes second. But on the other hand, the “national” government needs to protect and preserve the cultural or ethnic inheritance.

This is different than classical conservatism which argues for a limited government, allowing the culture to be shaped and formed however its free, individual, and autonomous citizens see fit.

Assumption #4: Human flourishing requires membership in a nation.

This is the idea that the highest kind of security and well-being come through national identity.

Nationalism puts all the cultural aspects of human well-being and common good at the center of political life (governmental policies).

Nationalism and Patriotism

So how is nationalism different than patriotism, one might ask>

Patriotism is gratitude and respect for the country we live in, without making the above four assumptions.

As Miller states, “We can patriotically love our country without believing it must be defined by language, ethnicity, religion, or culture; without believing that the jurisdiction of our government should perfectly overlap with the boundary lines of an imagined cultural group; without believing that our government should take upon itself the responsibility of protecting and promoting a universal cultural template of national identity for all citizens; without insisting on strong membership criteria for the nation; without insisting that our government engage in a competition for prestige with other nations; and without believing that the nation is essential t our identities or our fulfillment.”

What is the American national identity or American cultural entity?

To create a national identity, claims Miller, people often combine (or exclude) three sources: ethnic, civic, and religious.

Ethnic identity is a combination of language, culture, heritage, or ethnicity.

Civic identity comes from the democratic values of liberty and freedom, justice for all before the law, and other ideals expressed in America’s Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

We could understand the Civil Rights Movement as the triumph (at least in theory) of America’s “civil identity” against the racism of much of its “ethnic identity”.

And religious identity is self-explanatory, and in America has historically been Protestant Christian.

When someone has in mind “What makes America what it is?” they are generally affirming or rejecting a combination of these three elements.

Christian Nationalism?

But what about Christian Nationalism in America?

What is specifically “Christian” about it, besides the obvious fact that it is mostly Christians arguing for it?

That is for the next post (sign up below to get the next post via email).

Be sure to join the free webinar on “Are We A Christian Nation” on Thursday, Sept. 22nd with Dr. David Fitch.